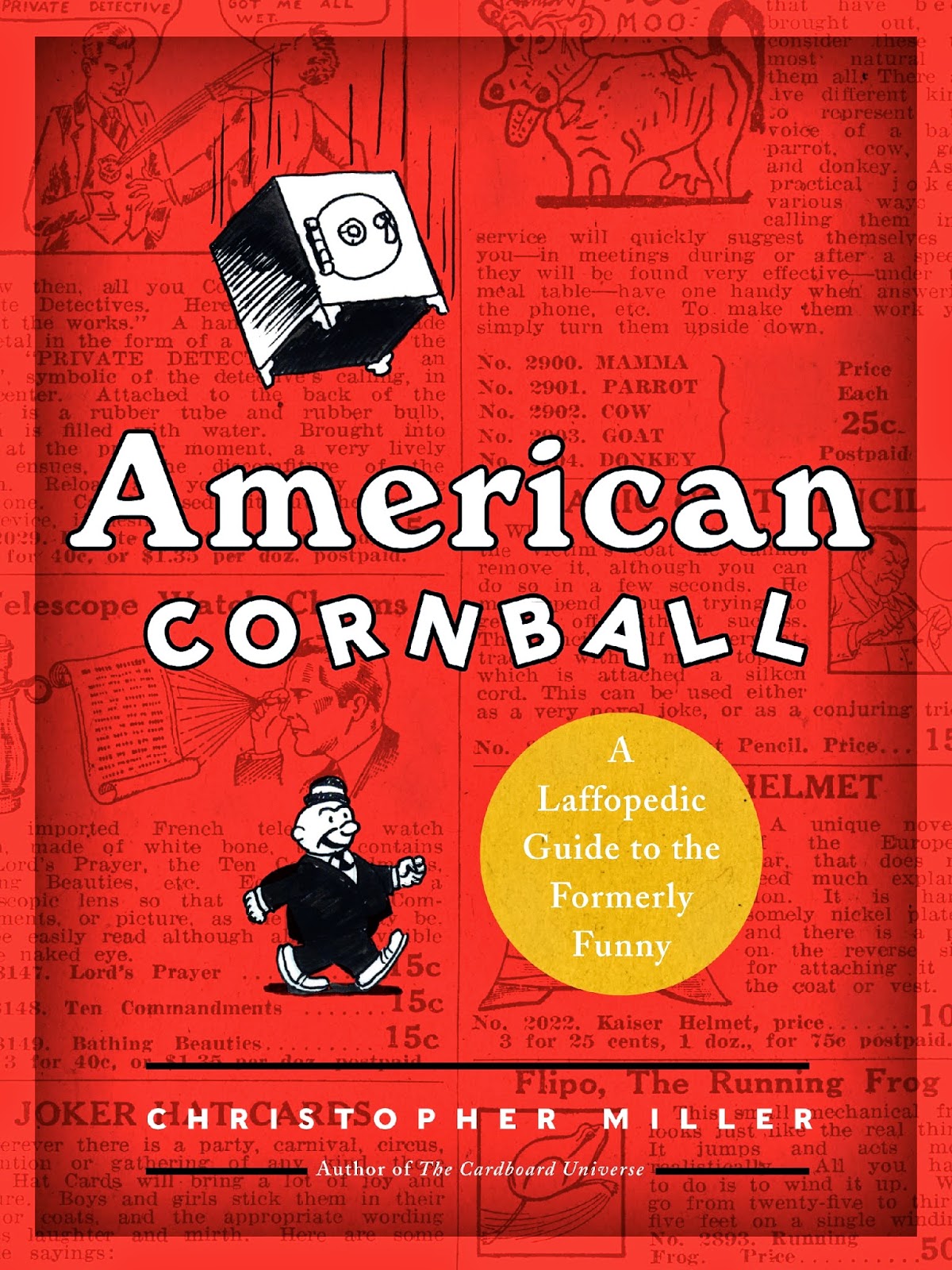

American Cornball: A Laffopedic Guide to the Formerly Funny, by Christopher Miller came as a delightful surprise. Arranged alphabetically, Miller enumerates the countless tropes so frequent in American comedy circa 1900-1966, and why they were funny and what they tell us about Americans of old.

Miller creates an artificial cutoff of 1966, citing anecdotally that the upheavals of the 1960s resulted in a seismic change in what America meant and, consequently, what it meant to be an American. One would think that this is an invitation for Miller – a professor at Bennington College in Vermont and the author of Sudden Noises from Inanimate Objects – to take potshots at the Great American Century. However, such is not the case at all, as Miller rightly sees the downside of our social “progress.” More often than not, it would seem to Miller that the America of the 1920s, 30s and 40s was a funnier, and perhaps, better place than the country we know today. (I would certainly agree.)

The book has entries on a wide array of laugh-getters, including falling safes and anvils, pratfalls, milquetoasts, flappers, hash, hobos, outhouses, rolling pins, castor oil, dishwashing husbands, nosey neighbors and noise – and that is just scratching the surface. Miller also talks about many of the formerly great venues for this humor, including full-page comic strips, radio comedy, silent movies, and of course, joke books.

Coming in at 544 pages, one would think that American Cornball more than overstays its welcome; however, one wishes the book was longer and some of the entries more detailed.

Miller’s particular genius is not just in enumerating instances of a comedic trope, but wondering why they were (or are) funny in the first place. Miller has keen insight into the human condition, and finds many of his observations in the arena of the ridiculous. Though not a philosopher like G. K. Chesterton (quoted, incidentally, in this volume), Miller’s worldview is that of an expansive humanist with a predisposition to the comic rather than the tragic.

The encyclopedia format keeps the observations loose and light, and this also proves to be one of the few flaws in the book: when Miller really has something to say (which is often), he is hamstrung by his format. One hopes that he will follow-up American Cornball with a collection of essays of greater depth and fewer topics, as there is much more for him to say.

But what he does say here is terrific and to be savored. I read through the volume with a goofy smile plastered on my face – and how could anyone resist a book that cites the Three Stooges, W. C. Fields and the Marx Brothers a source material?

Here is an example of Miller at his best, rifting on the subject of pain: There is, as far as I know, not one scene in all of Henry James where a character of either sex sits on a thumbtack. I haven’t read everything by Henry James, but I’ve read enough to know what the rest must be like, and nowhere do I see a thumbtack penetrating an unsuspecting buttock. Stubbed toes are also few and far between, if they occur at all. And unlike all those hapless dads on America’s Funniest Home Videos, the males in James’s arcadia never get it in the balls.

Good stuff, that, but better still, here he is midway on his discussion of morons: In our culture, “That’s not funny” really means “It’s wrong to laugh at that,” which is why we sometimes say it even while laughing. “That’s not funny” is only secondarily a report on the speaker’s true reactions, though it can be an effort to train those reactions. If you strongly disapprove of something and therefore insist it isn’t funny, that isn’t quite as dishonest as insisting that O.J. Simpson was never a great running back because you hate the psychopathic asshole he later became. No, it’s more like refusing to find an actress beautiful because you hate her personality. Given the determination, you really can suppress your sense of humor, like your sense of beauty. But if you say, “There’s nothing funny about mental retardation, and for the life of me I’ve never understood why anything thinks there is,” you must be either a hypocrite or a saint. Either way, you’ve clearly forgotten the jokes of your childhood…..

Then there is this, on farting: Before it became permissible to discuss farts openly, our forebears relied on all kinds of substitutes— from ducks to tubas, from foghorns to balloons. It may be that the fully lifelike simulation of farts became possible only with later improvements in sheet rubber, but in the pre-whoopee epoch it wasn’t necessary or even desirable for a noisemaker to sound exactly like the real thing; it just had to sound like something sometimes used to symbolize the real thing. Novelty makers are always boasting about how “realistic” their products are, but in this case, realism wasn’t wanted. Instead, aspiring practical jokers were offered a range of metonymies and metaphors. Even in our unembarrassed age, the whoopee cushion itself still claims to imitate a “Bronx cheer” or raspberry—not a fart but the imitation of one made by buzzing the lips in what linguists call a bilabial trill. (The reason that sound is called a “raspberry” is that it is or was cockney rhyming slang for “fart,” via “raspberry tart.”) The sound is the best simulation of a fart we can produce with our normal speech apparatus. In the early 1930s, when whoopee cushions took the world by storm, raspberries too were in fashion, at least on the funny pages—both Dagwood and Popeye had recourse to them now and then. A little later, Al Capp gave us Joe Btfsplk, the world’s biggest jinx, easily recognized by the small black cloud—a personal fart cloud? —hanging over him at all times. When asked how to pronounce Joe’s surname, Capp would respond with a raspberry, adding, “How else would you pronounce it?”

I loved American Cornball, and spent much of the past few weeks reading it aloud to my husband. This is a treasure for anyone interested in humor – and a perfect gift for those without a sense of one. Highly recommended – and Mr. Miller, more, please.